Despite delays, IDOT reconstruction plan to completely rebuild Wood Street by 2025

It is a three-mile project along Wood Street and Ashland Avenue, all the way from 138th Street in Riverdale, passing through Dixmoor, to 161st Street in Harvey.

In its over 90-year history, Wood Street has served as an anchor and a throughway bridging residential and commercial communities in Harvey, Dixmoor, and Riverdale.

It has also never been meaningfully rebuilt—at least, not until now.

“When this is completely done, the road is going to be rebuilt from the ground up,” said Maria Castaneda, a spokesperson from the Illinois Department of Transportation. “Compared to just surfacing, it’s going to be a great benefit.”

The overall $98.9 million improvement project will install new curbs, gutters, and replace water mains and sewers infrastructure by essentially rebuilding the road from its foundations. It is a three-mile project along Wood St. and Ashland Avenue, all the way from 138th Street in Riverdale to 161st Street in Harvey. It is expected to finish construction in 2025.

The reconstruction has been recently funded by Gov. Pritzker’s Rebuild Illinois, the state’s first capital construction program in more than a decade. In total, Gov. Pritzker is investing about $1.5 billion, spread out in six installments to advance infrastructure projects across Illinois.

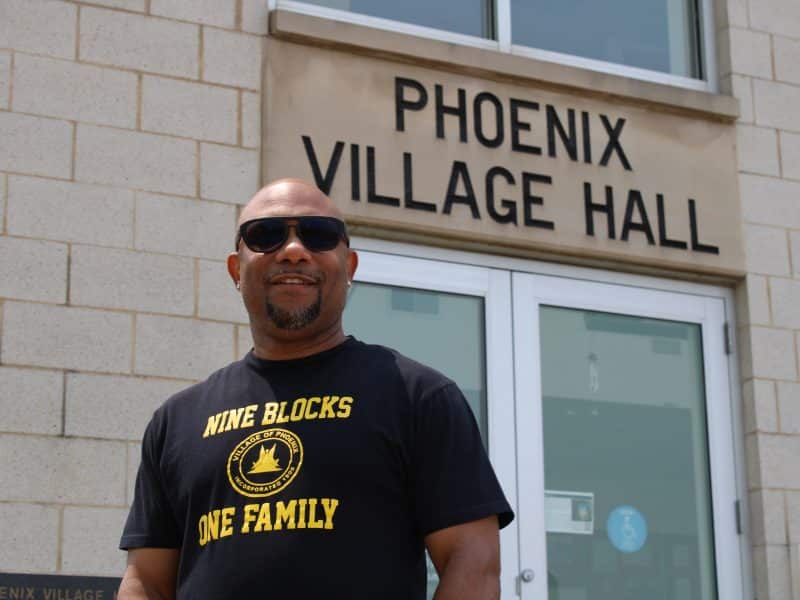

Travis Akin, spokesperson for Dixmoor, said the project has the potential to bring regional benefits and encourage collaboration and movement between the three areas.

“When you have a project like this that benefits everybody, everybody wins,” Akin said.

For Harvey, this new funding has meant the ability to break ground on a reconstruction project that had been in planning since 2012. At IDOT, both Castaneda and the project’s resident engineer, Aileen Tate, agree—the number one consideration for improvement hasn’t changed since then: safety.

“Right now, you don’t have curb[s] and gutter[s],” Tate said. “You really don’t have a safe place to walk from one corner to the next corner.”

Currently, Wood St. in Harvey has multiple potholes throughout its length. Poorly maintained sewers mean the road often floods, and there are sections along it where there is no walkable path.

These issues are familiar to Tate, who grew up in Harvey.

A Thornton alumna, Tate now works as a civil engineer and travels back and forth through Harvey. Occasionally, she runs into younger students and locals that know her, who she said react with excitement when they learn about what she does.

“I’m kind of lost for words, per se, but it feels good to be in my home community doing what I love every day,” Tate said.

She said she has a lot of passion for the project, which will be bringing ADA accessible ramps to Wood St. intersections, and also ensure that the entire street is well-lit.

But despite Tate’s strong connections to the community she serves, some in Harvey believe the project has had a too-long communication gap, and that it would have benefitted from more recent resident participation.

A slow start

The last public outreach event conducted by IDOT was a public hearing in 2014. Ryan Sinwelski, a member of Harvey’s planning commission, said he was hoping to hear more and be able to provide further input, but hadn’t had the opportunity to do so.

According to Castaneda, the project’s Phase I—the stage for public feedback and research, predates both her and Tate’s tenures at IDOT. The three year-long initial outreach phase was followed by a long designing and planning phase, lasting about seven years.

For Castaneda, the need for land acquisition in residential areas and contract approval meant that the second phase was slow going. On top of that, each phase of the project is funded separately, meaning budgetary concerns also came into play.

“I’m really glad they’re making the investment,” Sinwelski said. “But I was also bummed because I really wanted to get to them, and make a conversation about road diet.”

Road diet, a style of road construction which involves two throughways and a center two-way left turn, was Sinwelski’s preference for a safer approach to Wood St. in Harvey.

Instead, the project will involve road widening measures at intersections, allowing for two lanes in each direction and a fifth lane dedicated to left turns at every intersection. Along Wood St., about 30% of crashes are turning crashes, according to state data.

But for Sinwelski, adding lanes is not a solution to the safety problem.

“The roads are going to get wider, and people already speed way over the speed limit,” Sinwelski said. “And a majority of the path is residential, right? People have their houses right there.”

Sinwelski had hoped the reconstruction planning could have been steered toward a more walkable Wood St., with a bike lane and more room for pedestrians.

Though the reconstruction will not have a dedicated bike lane, the street will feature a multi-use path—an eight foot pathway on the westside of the street that will be shared between pedestrians and bicyclists.

Inspiring community efforts

One of Wood Street’s longtime residents is already feeling the impact of the road reconstruction: the UChicago Medicine Ingalls Memorial Hospital, on 155th Street and Wood St., has developed a plan to become an anchor hospital for the community. Its renewed efforts, in part, were inspired by the road’s reconstruction.

Paul Donohue, Vice President of Philanthropy and Community Relations at the Ingalls Development Foundation, was present when the governor broke ground on the Wood Street project. He said the hospital would benefit greatly from the road’s reconstruction, but now they needed to pay it forward.

“We’re looking at the long term and saying, ‘Okay, what does a revitalized and rebuilt Wood Street mean for the hospital?’” Donohue said.

UChicago Medicine Ingalls Memorial, which is celebrating its 100th year of service this year, is aiming to become an anchor hospital that would serve as the community’s cornerstone by tackling not only diagnostic needs, but addressing social concerns like greenspace, accessibility, housing, and food security.

The foundation, in collaboration with UChicago’s Harris School of Public Policy, conducted a study to assess exactly that. Graduate students at Harris School’s Policy lab developed survey questions related to the community and hospital, and began administering an ongoing survey. It has a near 60% response rate from Harvey residents along the corridor.

From October 2022 through April 2023, IDF, which helps steer the hospital, planned and designed an Anchor Hospital Community Development Plan in response to the road construction project. The study concluded that development along the corridor had the potential to greatly benefit the community, and that the Fund now needs to look for more investment opportunities, and develop further collaborations with community partners.

“This study is the first step down a pathway of opening up this dialogue about what to prioritize and where do we go from here,” Donohue said.

For Donohue, this community-building may have many avenues. For example, in 2008, a similar community anchor in Columbus, Ohio, the Nationwide Children’s Hospital, used its role in the community to help fund housing restoration projects to improve community health. These kinds of high-impact projects will serve as guides as Ingalls seeks to develop a community health corridor.

The IDF has already submitted requests for about $600,000 in grant funding proposals behind this plan.

We’re filling the void after the collapse of local newspapers decades ago. But we can’t do it without reader support.

Help us continue to publish stories like these