Water detention basin will reduce local flooding but displace some Harvey residents

Here’s what we know about the forthcoming “Harvey Flood Relief Project.”

Carlita Poole-Tingle’s mother passed away last spring. She and her family keep a portrait of their matriarch at their home on 153rd Street and Myrtle Avenue. It’s a black-and-white portrait, colored by her gentle smile and hoop earrings.

The image, and the home in which it sits, represent much of what they have left of her: memories. Her parents originally owned the home she, her husband, and their kids occupy. Poole-Tingle’s father and sister reside next door.

The two properties have been in the family since the 1970s. But those may be the next thing to go.

A new stormwater management project threatens to displace Poole-Tingle’s family. The Metropolitan Water Reclamation District is constructing a water detention basin on the block to address local flooding, requiring their relocation.

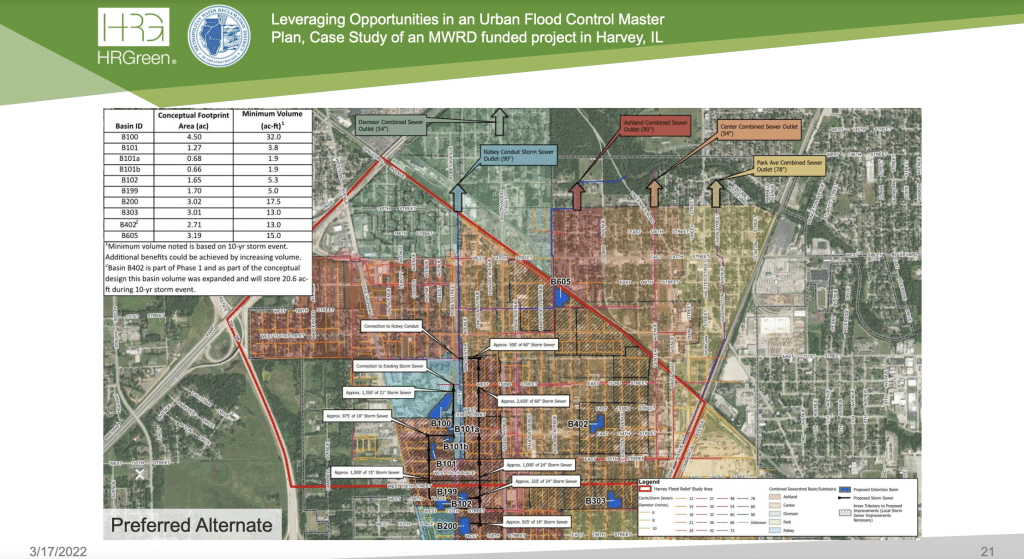

The Central Park Stormwater Detention Basin and Separate Storm Sewer Improvements project is a $9.85 million effort funded by the MWRD. It includes the basin and new storm sewers along 153rd Street and eight side streets, stretching from Paulina Street to Turlington Avenue. 209 commercial and residential structures will see flooding alleviation over the next century.

Poole-Tingle, other impacted residents, and allies spoke out against the project at the Board of Commissioners’ August meeting. Poole-Tingle’s father, 88, wants to be cremated upon passing. “‘I want you to throw them out in the backyard because I want to be able to see what’s going on in my house,’” she recalled her father’s wishes for discarded ashes.

Many, including newly minted Alderwoman Colby Chapman (2nd), are chiding communication lapses. The mayor’s office had already co-hosted two meetings with MWRD and impacted residents before Chapman learned her own constituents—renters, homeowners, seniors, non-English speakers, even children—would soon be displaced.

“In most instances, you want to be very proactive. In a lot of ways, I’m being reactively proactive,” Chapman told the Board, “but I stand at the helm of leading the front for our 2nd Ward constituency and ensuring that they have a voice that’s being heard by you all, at large.”

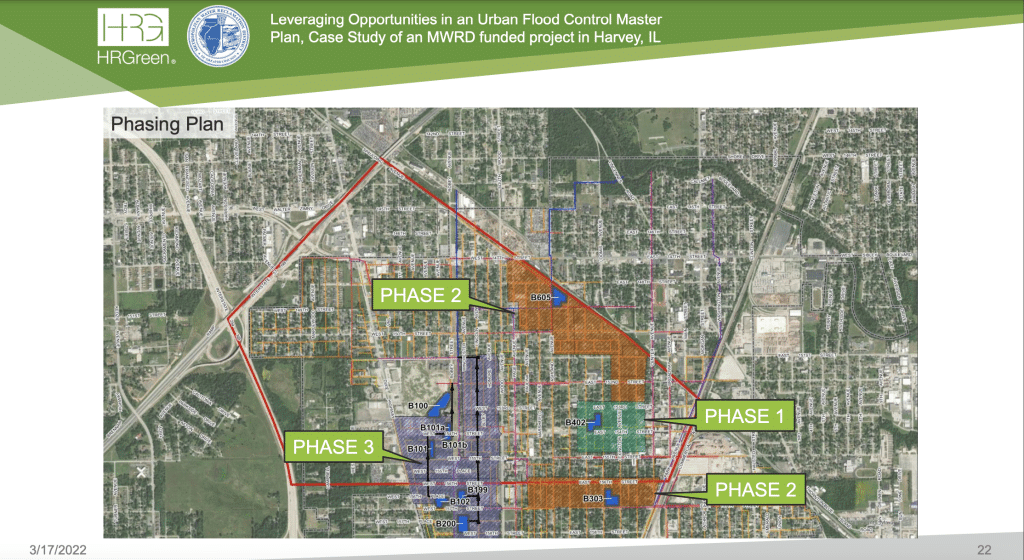

The communication breach underscores a key issue: according to a District proposal from March 2022, this is the first of a three-phase project, also known as the “Harvey Flood Relief Project.” It’s replete with additional basins, elevating concerns about residential displacement throughout the 2nd—and 3rd—Ward. The District and city officials have been coy on those details.

Now, residents are fighting to remain in their homes and for transparency and accountability from Mayor Chris Clark and the District.

What we know about the project, so far

Harvey’s flood relief efforts have been five years in the making. Harvey officials applied for flood relief assistance to the residential area south of the CSX railway in 2018. That initiated a conceptual planning study of a 2.4 square mile area in the city.

HR Green was authorized to perform preliminary engineering work in July 2019. With the change in mayoral administration, the District held two kickoff meetings with city officials in fall 2019, Director of Engineering Catherine O’Connor wrote in an email to Chapman and impacted residents.

City officials desire to transform the long vacant Ascension-St. Susanna Catholic Church into a park on the block’s southeast corner, tentatively dubbed “Central Park.” The water pond will be dual-use, equipped with new walking paths, limestone steps, and green space.

The District circulated a survey to Harvey residents in 2020. Of 413 respondents, 66% reported flooding, according to Dylan Walsh, Senior Civil Engineer in July. Roughly 52% reported structural flooding, such as water in the basement or crawl space, he added.

“[…] It was determined that while there’s widespread flooding in the City of Harvey, the area in the southeast portion experiences the worst flooding,” Walsh said.

The basin’s current location is ideal to allow for water runoff toward the new Wood Street storm sewer system, Walsh said. The state-funded $94 million Wood Street project will replace curbs, gutters, and the main sewer line along the corridor.

Clark’s office and the District sent notification letters to residents in June. In July, the District and mayor’s office held three meetings—two with impacted residents and another citywide, where Chapman eventually learned of the displacement.

The District still needs to finance the effort. It already applied for $5 million from the Federal Emergency Management Association last year. Its application is currently under further review but not approved, according to an official announcement from August 28.

According to O’Connor, possible study results and a preliminary draft report, along with design plans, were sent to city officials for review in October 2021. The next month, the Board approved the final design contract. The District held another kickoff meeting with Harvey officials weeks later, according to O’Connor’s email.

The city purchased the church and school campus in January. In February, the District approved an intergovernmental agreement with Harvey for the effort.

There are 31 parcels of land, 15 of which are occupied. Critics decry the delay in notification, but it might not have been efficient to tell residents about possible displacement considering the Board hadn’t approved legal paperwork to seize the properties.

In April, upon recommendation, the Board approved a right-of-way ordinance to initiate property seizure.

Construction will begin next summer and take an estimated 18 months.

The District will retain an appraiser to assess property values. Residents can hire their own but that won’t be covered by relocation assistance monies. They will receive a form of rental or purchase assistance, depending upon their circumstances.

Any undocumented residents would not receive relocation assistance, federally ineligible.

Political influence from City Hall

Condemnation projects seek private property for the public good. The detention basin initiative, however, is partly influenced by the Second Floor.

Urban flooding is not a fictitious problem in Harvey. The city’s connected sewer system is over 200 years old. Climate change is worsening. The HWH previously reported urban flooding—and communication faux pas—in the area along 148th Street and Main Street.

A combination of factors, including “hydrologic and hydraulic (H&H) modeling, resulting inundations, and a review of vacant/city owned parcels,” led engineers to identify 153rd and 154th Streets along Myrtle Ave. as a possible detention area, according to O’Connor.

“However, the exact location of the basin was determined in consultation with the City of Harvey over the past few years and was driven by their desire to develop a Central Park near the former St. Susanna,” she continued.

Myrtle Ave. residents have been careful to say they actually welcome the mitigation efforts. They just want the basin moved to prevent displacement. But O’Connor cited higher costs and lower public benefits for why it’d be a hassle to move it.

The proposed Myrtle Ave. basin isn’t located in the flood zone, according to a FEMA regulatory flood map, but close to it.

However, it’s 1.5 miles away from where officials reported flooding woes to the District.

In June 2018, city officials submitted a conceptual planning request for flood relief around 147th and Wood Street, according to District records. Nearly 130 structures would be affected, according to the request.

That’s dead smack in the flood zone. And dovetails directly with the state’s rebuild of the major artery connecting Harvey, Dixmoor, and Riverdale.

Both aforementioned intersections are part of the Calumet Region, where Cook County is funneling federal COVID-19 dollars into programs like StormStore and RainReady to address urban flooding.

Little is immediately known about the “Central Park” vision aside from what the mayor said during the initiative’s citywide announcement.

Voices in the city want more recreation, farmer’s markets, basketball and tennis courts, and even public art. “We are now gathering the space so we can do that,” Clark said.

That’s been an uphill battle. Black mold, for instance, forced city officials to shut down the community center in 2019, which Clark revealed the city never actually owned under the prior administration. “I couldn’t believe that people were actually letting their parents, grandparents, and their children go in that place,” he said.

Clark also wants to build a civic center, modeling after more affluent areas that have that type of infrastructure.

His comments suggested that the financing to build these projects is still forthcoming.

The park will be located just within the FEMA flood zone.

Citywide criticism and suspicion

“How was Harvey selected? I think it’s ‘cause they think I’m great. And they finally got somebody that they can actually talk to and have a conversation with,” Clark said to applause when a resident asked how Harvey began receiving funding for stormwater projects.

Prior administrations were poor to talk to, Clark added.

“Absolutely. It’s you, Mayor,” echoed O’Connor.

Constituents might beg to differ.

Murdenna Coleman, a 3rd Ward resident, told the Board she was booted out when she stumbled upon the first meeting with impacted residents at City Hall, July 6. City Administrator Corean Davis snatched a flyer from Coleman’s hands before Clark had building security escort Coleman out, sources told the HWH.

“We are surprised and saddened to hear about the lack of communication,” said District President Kari Steele as she and the Board listened to residents’ qualms.

The backlash has been swift. Residents are lambasting city and District officials. There’s an online petition demanding a halt to demolition.

One critique rings loudest: the District is now a complicit actor in shourds of secrecy in the Clark administration, which some critics say has embraced an Eric J. Kellogg-esque code of conduct to keep residents ill-informed—even alderpersons.

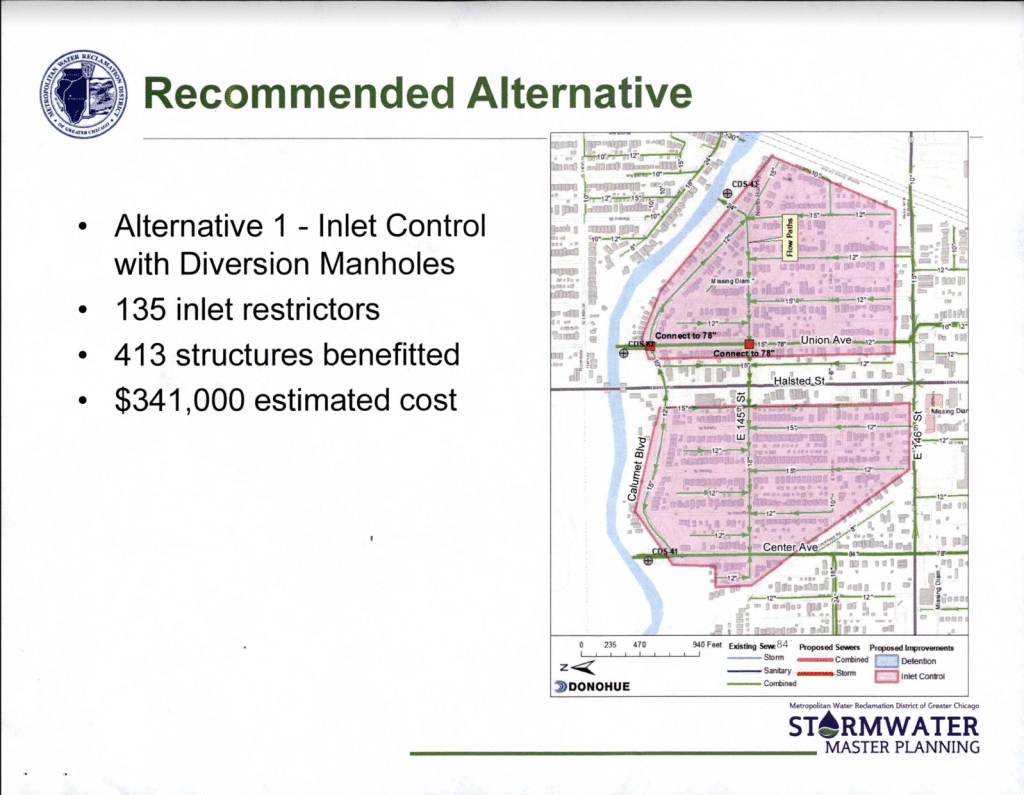

In June 2022, the District missed a key opportunity to reveal critical project details. A District representative delivered a presentation to Harvey residents highlighting three initiatives.

The “South Suburbs SMP” seeks to develop an inlet control system along 145th and 146th Street, preventing runoff from overwhelming the city’s combined sewer system. An estimated $341,000 cost, 413 structures in the area would benefit, according to the presentation.

They also mentioned the District would perform an at-risk assessment of Harvey’s sewer system thanks to $3.5 million in federal funding.

They briefly described the number of structures to benefit from the “Harvey Flood Relief Project.” There were no slides with schematics or cost estimates about it even though the final design contract had been approved seven months prior.

The culmination of these efforts will take upwards of 20 years to alleviate identified flooding woes, according to Clark.

Black-owned law firm Neal & Leroy will help seize land. N&L is a premiere firm used by governing bodies in Chicago for eminent domain and condemnation. It helped secure tracts in big projects, such as O’Hare Airport, Wintrust Arena at McCormick Square, and the White Sox Stadium.

Co-founder Langdon Neal has secured big clients then lobbied them for other high-paying contracts, the Chicago Tribune reported.

We’re filling the void after the collapse of local newspapers decades ago. But we can’t do it without reader support.

Help us continue to publish stories like these