Harvey schools continue to adapt to pandemic-driven bus driver shortage

A lack of bus drivers is creating new challenges for Harvey schools, like strains on academic support programs and accessible education. What are districts doing to resolve the problem?

This report was made possible by the National Association of Black Journalists and Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative Black Press Grant program.

Twelve-year -old Jiovanni used to wait on the intersection of 154th and Myrtle for the morning bus to go to school. But when faced with uncertain delays and ghost buses, his mom had to make a decision.

“I started driving him to school,” said Shannon Delgado, his mother. “Because I didn’t want him standing out there knowing that the buses don’t always come on time, or he’s just standing there and the buses don’t even show up.”

Delgado’s son goes to Gwendolyn Brooks Middle School—and for her, the reliability of the bus route is a matter of safety.

Since the pandemic began, there has been a nationwide shortage of bus drivers, leading to delays and complications for school transportation. And though one school year has passed, for some Harvey schools, arranging for transportation to get children to and from school is still a struggle.

Caught in year-long contracts with bus companies that have been unable to supply an adequate number of drivers, school districts are still struggling to get their transportation back to normal.

“At the beginning, it was just a circus,” says Dwyane Bearden, the president of the Faculty Association of District 205. Buses were delayed, or missing, and arranging the routes to ensure that all students were being picked up and dropped off was a challenge.

The first semester after in-person classes resumed, in the 2021-22 school year, Bearden received reports that one student went as far as to request an Uber ride just to get to school—in another, similar situation, one student simply didn’t attend class at all.

Bearden, who governs the faculty union encompassing Thornton, Thornridge, and Thornwood high schools, describes what’s happening as a “no-win” situation. The nationwide bus driver shortage means that the transport companies that schools contract with for routing services cannot provide flexible support, he said. On the other, schools themselves do not have the flexibility to change service providers once they are locked in for the year.

For Bearden, the key lies in making sure the bus companies are effectively staffed. But that challenge has been hard to answer—at least for Greg Polan, the president of Alltown Bus Service.

“It’s been very very difficult. It’s been a real, real nightmare,” Polan said. “We’ve lost a lot of drivers and they haven’t come back.”

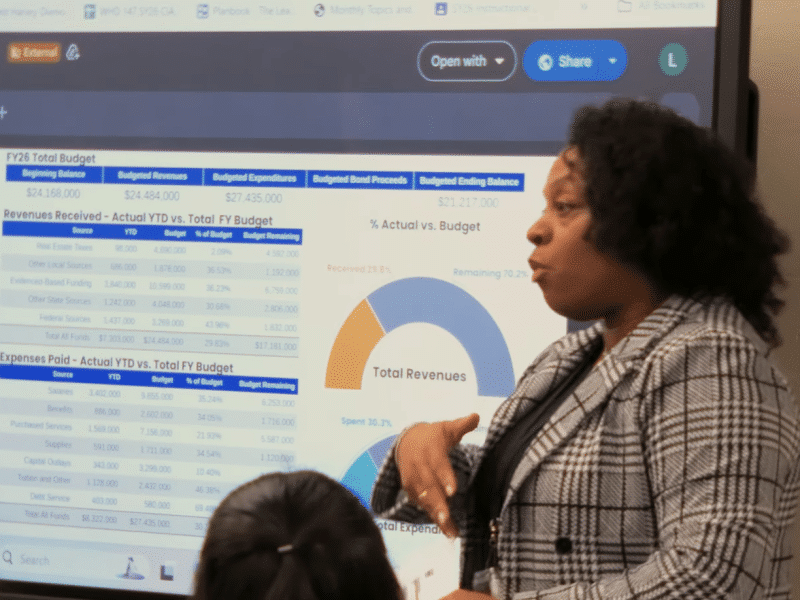

ABS supplies bus routes for schools in District 152 and 147 in Harvey, including to Gwendolyn Brooks Middle School, and several other school districts in the Chicagoland area.

The requirements to be a school bus driver are very difficult to meet, Polan said. Candidates have to go through two to three tests, receive a commercial driver’s license, commit to multiple drug and alcohol screenings, have their fingerprints taken, and take regular refresher courses.

Feeling that the barriers to entry were steep, Alltown Bus Service has even hired a recruiter to help with their process. They’ve also offered to train new recruits free of charge.

“Despite this, we’ve gotten very few applicants across the board,” Polan said. “We’re still having trouble hiring good drivers.” The company has not increased baseline wages or changed their benefits packages other than the annual bonus, Polan added.

‘Many kids needed that’

According to reports Bearden received from teaching staff and professionals working for the schools in his district, the lack of effective bus management has affected athletic programs, attendance, and even academic support programs.

At Thornton Township High School, English teacher Kelly Cunningham said some of these after-school programs are key to her students’ success.

“All of our support programs—which I always thought were the highlight of Thornton—took a really long time to get back in place,” Cunningham said.

For the first year back, Thornton did not have buses that would run after teacher office hours at 3:30pm, or for the additional academic support, that would typically run at 4:30pm. The resources that should have been there for the students weren’t in place, and Cunningham said she feels like some students are even more behind as a result.

For Cunningham, many students at Thornton benefit from after school support resources like their afterschool Homework Lab and weekend support groups. Due to the lack of available buses, the former only restarted this semester, and the latter restarted even more recently.

“It took away the opportunities where they could get extra help,” Cunningham said. “So many kids needed that.”

Across Illinois, the school bus driver shortage has been impacting accessible education.

Frank Lally is an education policy analyst at Access Living Chicago, a local nonprofit that provides care and advocates for people with disabilities. Lally said he has been working to help illustrate challenges faced by students with disabilities and get districts and lawmakers’ attention.

In some cases that Lally had worked on, children were arriving at school an hour before classes started, or had been put on hours-long bus routes that did not show up in time for morning classes.

“This kind of delay or complication can be seriously detrimental to students with disabilities and to all students in general,” Lally said.

Public school districts have a legal requirement to ensure bus services for students with disabilities, something that Lally noted large districts like Chicago Public Schools still have to meet. After the 2021-2022 school year, Lally had hoped that schools across Chicago would have been better prepared to tackle the driver shortage, but he said that many responses felt lacking.

For example, CPS said in a February meeting that it has provided routes to 97% of families in need. However, Lally notes that in some cases, CPS has simply provided a $500 monthly stipend to families it was unable to route.

“It’s great that they are offering that,” he said. “But I personally don’t think that it is enough to cover what it would take for a parent to drive their kid to and from school every day. “The districts had a whole year to plan out the routes,” Lally said. “So that’s been frustrating to see.”

New solutions and room for growth

Recovery from the pandemic—for the students and the schools themselves—has been slow, but steady.

Akela Ray, a Thornton senior, said the school has been better at communicating bus delays to the students since the pandemic began.

“I actually think they’re better now,” Ray said. “When it’s time to leave school, they send out emails to tell us if our bus is delayed or combined.”

District 205, which encompasses Thornton, Thornridge and Thornwood high schools, implemented an online bus schedule tracker in September 2022. D205 contracts First Student Bus Services for its transportation needs.

The best improvements occur in school districts that are willing to work with bus companies and help provide innovative solutions, Polan said. He added that Harvey bus drivers are some of the most enthusiastic that he has worked with, and that the majority of them came back to work as soon as restrictions were lifted.

“We worked with the districts,” Polan said. “One of them made a bell time change to accommodate what they wanted to do, and that helped a lot.”

For schools, a temporary fix could look like changing the time students come (or leave) to school to be later or earlier, so that a smaller number of buses can be used to serve multiple schools.

But it’s been a full school year that class is back in session, and Brooks is still releasing children 30 minutes earlier—at 2:30pm—so that the buses can pick up students from another route for a second shift. Similar adjustments have continued with other districts.

Though certain special education programs have restarted since, Cunningham worries that it was made available too late into the academic year, and now the students are already a year behind.

Ahead of the board elections, Bearden said bussing is an issue of student safety and therefore a priority going into the next school year. For Bearden, a public meeting between the district and concerned parents about what is being addressed and how it is being addressed is necessary to ensure open communication.

“I know that the district has been using whatever resources they have to try to fix this,” Bearden said. “But it still has not eliminated the problem.”

We’re filling the void after the collapse of local newspapers decades ago. But we can’t do it without reader support.

Help us continue to publish stories like these